Theft, Waste, and Puzzles: How I Design

I hoard information but I don’t see the point in keeping it from others, so I’m going to elucidate a bit on the grand secret of my design process. I try to get this sort of thing out in dev blogs and writing series on my CCG designs, but I feel the need to get even more meta on the subject.

First Step: Everything Starts with a Core Concept or Idea

Some cores are abstract like in the case of Mobius Flip: I wanted to make a Trading Card Game based in time travel. That’s a ridiculously high level and broad concept. Some cores are precise like the one I’m wrestling with now: How does movement and existence present itself in my MUD?

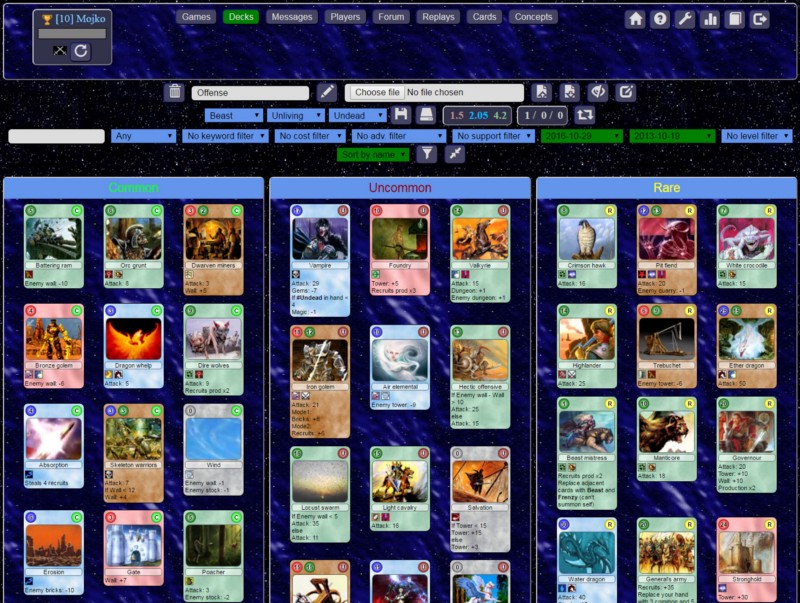

The core can’t change. You might end up with a completely different core by the end but that is more of a conceit to shifting interest or viability. My TCG Siege! started as the core of making a deck building variant of Arcomage (the card game inside of Might and Magic VII). It ended up wildly different only because I found myself violating the core concept too often to make things interesting or playable.

Arcomage via arcomage.net

Arcomage via arcomage.net

That’s the first lesson: Not every idea is viable — or interesting — and to be quite honest ideas are cheap, so go with the ones that are both. Long ago I introduced full on limb severing mechanics to my MUD combat system. That’s an interesting idea. It became quickly apparent that it wasn’t a viable one. Technically it worked; it was functional. However it wasn’t even not fun; it was pure anti-fun.

So back to the core concept at hand: How movement works in my MUD. Here’s where puzzles come in. I see concept and systems design as a puzzle. A massive floor puzzle with N number of pieces. Your core concept is the entire set of outer-most pieces. You know, the bit you do first because you can rely on cordoning off every piece with a flat edge to make a quicker start. Everything from here fits inside the “frame” of your core but how do you start? Just like with a large puzzle you collect the pieces into a pile and turn them all face up so you can see them.

Second Step: Making Problems

Implementation is about problems. There are inherent problems to solve in every design: How will the user interact with this, how will the user know how to interact with this, and the myriad of what will happen when X does Y? It isn’t just about solving problems, however, it is more so about finding the problems that need solving.

So you lay out your problems face up. Don’t start solving them until you’ve got as many as you can think of in front of you.

Third Step: Steal Everything

Someone has dealt with this problem before. While it might be derivative to just wholesale copy an existing design there are lessons to be learned in successful and unsuccessful products.

In the case of the MUD most of my problems were things I wanted to see done differently because this is an iteration but there is a design trap in iteration. Long ago when City of Heroes was still around much the original design team, Cryptic, decided to do their own superhero genre MMO-light game. They went about it in the worst way possible. They went full ham on negative iteration. There are two types of iterative thinking: improving and dreaming.

Dreaming fueled, at least initially, how Champions Online (CO) was designed. Agents of Cryptic literally trawled the City of Heroes forums polling people for what they wished they could have always done in that game. CO became “everything you could never have in City of Heroes”. That’s a trap.

Champions Online via softonic.com

Champions Online via softonic.com

You can’t follow an antithetical design because it has no bounding. It creates an endless stream of what-if pits to fall into and poses design elements against one another. You can’t start the conversation from the point of “what didn’t work” because everyone will have not only differing but opposing opinions on that subject. In City of Heroes I loved playing hard controller archetypes like Gravity, but many many people hated grouping with grav controllers, and some hated the very concept of controller archetypes entirely. Designing something out of what something else never was will deliver a mashed pile of concept spaghetti.

The first year of development saw little major change to how movement would work and present itself in the MUD design. I was making a MUD so it would be an open world of connected boxes (rooms). The problem I was solving, however, was one of size. I wanted an environmental simulation to scale which meant, to me, literally millions of rooms. The obvious solution was to just do it; I’d make the absurdly huge world. I did not realize, however, that I wasn’t improving anything I was just bolting more problems onto the original one. I could get on with how I came to a solution but that’s for a different article. It brings us to the fourth lesson in design: the trash bin.

Efficiency is a major cultural force in the United states. Unfortunately more often than not we sacrifice efficacy for what seems like efficiency and no matter how similarly those words are spelled they are entirely different concepts. Throwing ideas away is one thing but tossing over a year’s worth of work towards one of those ideas is a hard pill to swallow.

Instinctually, when I came upon new solutions to that original problem I tried to cram the square peg I had built into the new round hole. I just need to shave the corners off, right? So after a year’s work I spent another 6 months trying to “not waste” my prior efforts and ended up wasting even more effort in the end.

I kept forgetting the third rule. I didn’t feel the need to steal ideas because I already had one. Still it stems from the second rule: lay everything out in front of you. That applies to problems as well as solutions.

As it happens I eventually had an epiphany: I had to steal ideas to make this work. If I was dead set on having (and solving) the problem of a truly massive world and the only true way to get there was to comprise the world of mostly procedurally generated space I had to review what I knew about procedurally generated worlds.

I like to think of massive online worlds as contiguous. MUDs and the “AAA” graphical MMORPGs like Everquest and World of Warcraft have these vast environments. When you think about it, though, piecemeal worlds like ARPGs and instanced worlds like Guild Wars have vast environments too; they just present themselves differently in places.

Diablo and Sunless Sea immediately came to mind for me. All three entries in the Diablo franchise are well known for piecing together relevant content into randomish generated areas accessible from static towns/camps. Sunless Sea essentially divides its content into 2 bits: storied places (ports) and open world (the Zee). In both cases you have to traverse areas with unknown layouts to reach story point destinations. You derive direction and supplies from these static places and “play the game” within the rest of it.

This brings us to…

Step Four: Problems and Solutions Are the Same Thing

If every puzzle piece in this metaphor is a problem the only way you can solve these problems is by connecting them to each other. Fitting problems together creates solutions.

Stealing environmental concepts from Sunless Sea and Diablo created more problems which deigned to break out of the frame of my core design. The world won’t feel vast if people can travel from “town” to “town” without interacting with the environment. It’d be like the MMORPG equivalent of suburban America. People would get in their car and drive from point A to point B never really interacting with the path in between unless they absolutely had to. I could take the tact I’ve seen so often in game design: just yell at the players for playing your game “wrong”.

Sunless Sea via steam

Sunless Sea via steam

This was a problem but it was also the solution I never knew I needed. The design suffered for quite a while in not knowing how fast travel was going to function. With a vast world fast travel is essentially necessary but if you make it too easy players will advance without knowing how the world truly works. If it is too obtuse or costly players will never use it an eventually abandon your seemingly single-player-experience world.

Vastness was solved by introducing the concept of Zones. Similar to Sunless Sea in a roundabout way you can be in a Zone. While in the zone you travel to other connected zones or you can enter Locales. Locales are collections of those Rooms I mentioned before: the real part of the game world. Manually constructed and static or procedurally generated maps of rooms you can explore and interact in.

More often than not you’ll only see zone-to-zone connections after you’ve found the “exit” in one of the locales. If you enter The Dark Woods zone you’ll be presented with a nigh impenetrable forested area with the only option being “enter the woods”. Inside the procedurally generated section of woods exits to permanent locales and other zones may spawn. If you find and use them those exits will also appear at the zone level.

Thus, instead of having to create an engine that would procedurally generate several million rooms out of an untold amount of configurations at the start the world is now ~90 zones that need configuring and as many on-demand generated sets of rooms as the players are actually using. The vastness problem ended up solving the fast travel problem. Additionally managing a fluctuating amount of spaces will be much easier than trying to manage millions of always-existing spaces.

Stick to your core (or find one worth sticking to), don’t follow anti-design patterns, don’t be afraid to throw things away, steal everything you need and try to make your problems solve each other.